It’s common to view these preoccupations as being at odds with one another—and to think that managers who respond with compassion in one moment and exhortations in another are trading in mixed messages. In my view, there is no inherent conflict—and any tension between the two aims is a necessary tension.

Psychological Safety

Psychological safety has many aspects, but three that I see as particularly important in a business context are:

1. Making it okay to make mistakes—meaning cultivating an environment where people feel comfortable exposing, discussing, and learning from their errors.

2. Recognizing, even when it’s inconvenient from a business perspective, that every team member is above all else a human being with a private life that—especially during personal crises but also for part of every day—must be given priority over work-related concerns. (The rationale, in case it needs saying: well-organized colleagues can cover for one another, while the myriad roles we all play in our personal lives tend to defy re-assignment.)

3. Being straight with people: no employer can make life’s (increasingly?) bumpy ride secure, but every employer can be clear about what they know, what they don’t know, and how they go about making decisions.

Business Results

At any company that is not an independently-funded vanity project, every role exists—or at least endures—because of some economic logic: if you do X, it will make business sense to pay you Y. The uncomfortable flip side of that is: if you don’t do X, it likely won’t make sense to continue paying you Y. This has nothing to do with being tough. This is just math: in any well-managed business, every role has to earn its keep by solving certain business problems and delivering certain business results. In other words, every person has to deliver the ROI (return on investment) that was assumed when the role was created.

Managers who a) make clear what exactly earning one’s keep looks like b) point out performance gaps in time for an employee to address them and c) provide support and coaching along the way are doing the people on their teams a kindness, however uncomfortable it may seem. The alternative is to be blindsided by a firing, something that happens but ideally shouldn’t. (An all-too-topical side note: layoffs—which are very different from performance-related firings—do typically blindside people. It’s part of what makes layoffs so emotionally devastating and why it’s incumbent on leaders to grow their companies in such a way that radical “corrections”—a clinical term for something that packs a terribly human punch—won’t be necessary. That said: I get that managing growth perfectly is WAY easier said than done. Here at Steyer, we’ve certainly had our share of missteps.)

My Main Point

In a high-performing organization, psychological safety is essential. Not only is it good for everyone’s nerves (reason alone to nurture it); it also helps create an environment of learning and continual improvement. Furthermore, supporting employees as the human beings they are—with rich, sometimes complicated personal lives—and operating with maximum transparency is both plain right and plain smart: the best talent, all of whom have the confidence and skill to work at any number of places, may choose to stick around longer than they otherwise would.

That said, psychological safety is not the same thing as job security. Job security, which has become more tenuous over the last 40+ years for various structural reasons, depends mainly on one thing: making the numbers work. This in turn requires a culture of accountability, both at the individual level and at the team level, routinely comparing business results to expectations and course correcting as energetically as needed.

At least that’s what I think. What do you think? Do you see these two aims as compatible? Can a work environment be both supportive and rigorous? I look forward to engaging with you—I respond to every message I receive within a week—and thank you, as always, for reading!

Kate

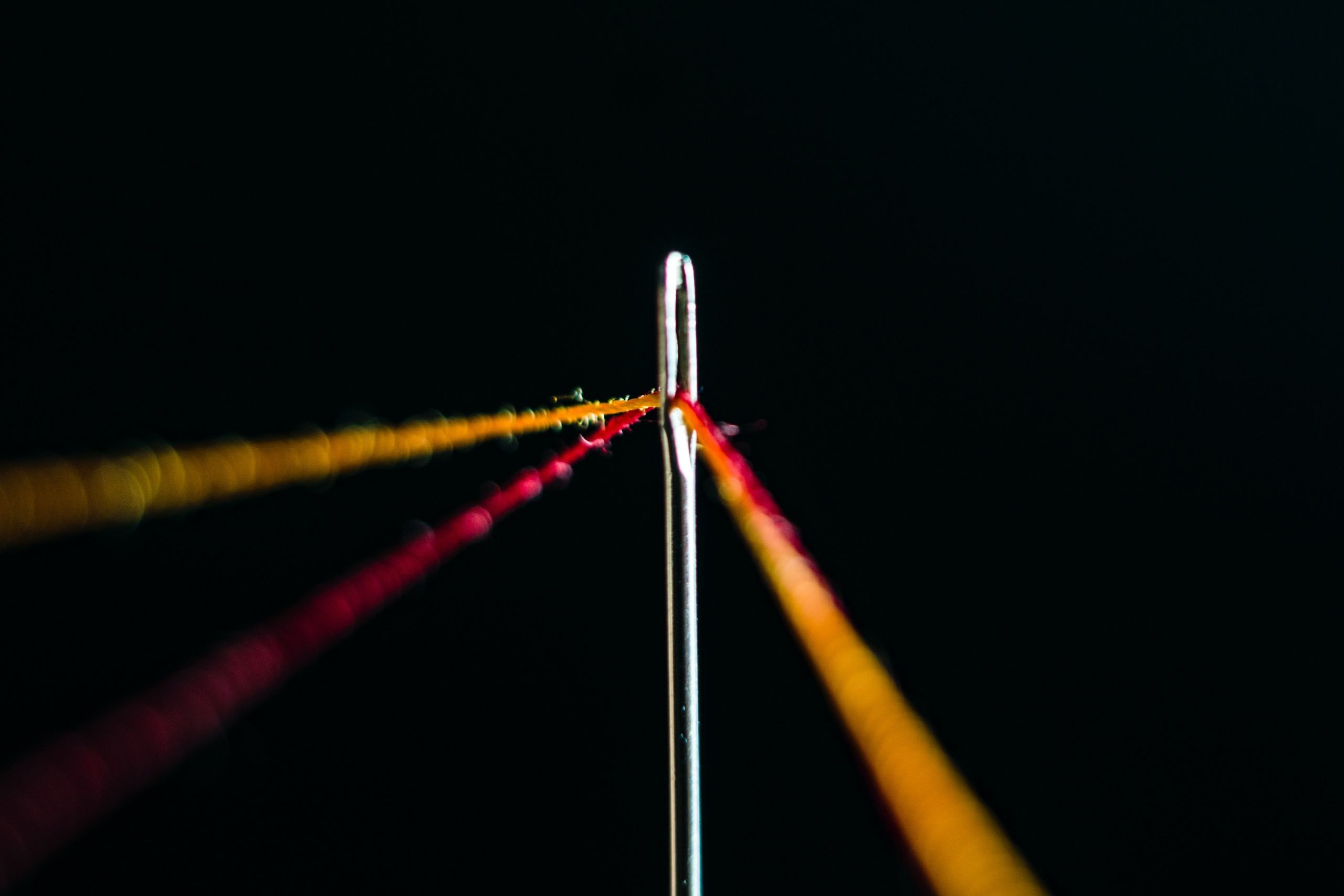

Photo by amirali mirhashemian on Unsplash

Hello from Steyer!

Hello from Steyer!